In this blog, ITX EVP of Innovation Sean Flaherty explores the power of Vision to help product teams realize their full capabilities.

This blog is a refreshed version of the original, which was first published February 15, 2022, on Medium.

Getting the Vision Right is Hard Work – But It’s Vital to Team Success

A great vision is one that unlocks human potential and creativity by painting a clear picture of what is possible. Stewarding, adapting, and continuously refining the product vision is the top priority of successful leaders because it is a key driver of the organization’s strategy.

Vision is really hard to get right, but there is a pattern that I have found in the work of great leaders that can be replicated (discussed below). It can help us craft and steward better, more motivating language for our visions.

A great vision is one that unlocks human potential and creativity by painting a clear picture of what is possible.

When a vision is well articulated, understood by the team, and shared across stakeholders, it motivates people to apply creativity in their work – the kind of creativity that delivers value by driving toward the future described by the vision.

When we combine a clear vision and a motivated team to achieve it, we put in place a healthy, powerful strategy.

When a group of motivated people shares clarity and alignment on the strategic output they seek to achieve, they create a foundation from which to achieve great clarity around both the strategic inputs needed to accomplish the stated goals.

A clear vision also helps us attract the right people to join the cause – i.e., those who care about solving the same problems for the same people that you have defined in your vision. It becomes a lot easier to realize we have the wrong butts in seats throughout their organization.

When a vision is weakly constructed or poorly articulated, motivation languishes. The team will have a poor understanding of the capabilities required to achieve it, resulting in confusion, frustration, and waste.

A shared vision is a powerful part of any group’s culture. Similar to other components of an organization’s culture, the vision’s primary reason for being rests in the language used to express it. This fact makes it critical for leadership teams to communicate the organization’s vision clearly and frequently.

Done poorly, teams experience one of two problems. They either lack clarity around whom they are serving, or they are solving the wrong problems.

Done well, clarity of purpose serves as the foundation for directional, strategic decisionmaking and as the primary guardrails keeping the organization on track toward a meaningful and motivating goal.

A Definition for Vision in Business

A distinct pattern of success exists in our space; it is demonstrated in the language used by the greatest leaders of our comparatively brief history and by their most ardent followers. They embrace an inherent understanding of who is being served and what problems are being solved. What’s more, they set the context for the work being done. In their most powerful forms, they share a crystal clear understanding of what success looks like. Taken together, these three components motivate the people doing the hard work that brings the vision to life.

In simple terms, a great vision paints a picture of how the world will look for the people we serve after we have solved problems for them, together.

Abraham Lincoln was known to be incredibly purposeful with the spoken word and worked hard to get them just right. We remember his speeches because of their clarity, brevity, elegance, and his almost lyric delivery. Lincoln’s Gettysburg address, for example, totaled only 272 words and required fewer than 2 minutes to deliver. Yet it remains among the most significant speeches in his or any presidency.

He chose words that connected with those he was leading, which aligned them around the future he sought to create. Winston Churchill did the same, through language, rallying his nation to beat back the Nazi assault through “the spirit of the British Nation… who have been bred to value freedom far above their lives.” Mother Teresa created an enormous shift in humanity by painting verbal pictures of a more humane and more empathetic world and showing us how it is possible to live into them.

I alone cannot change the world, but I can cast a stone across the waters to create many ripples

Nelson Mandela ended apartheid in South Africa through his vision for an authentic democracy. This is the pattern that can be seen in the language of the greatest leaders of our collective history.

Not all of us are trying to change the world in the same way as Mother Teresa or Nelson Mandela, but each of us wants to believe that our work matters to the people we are serving. We want our efforts to have meaning and we can take a lesson from the playbooks of great leaders about how to create an environment that improves our chances of success.

The pattern modeled by these great leaders is not complicated. It lies in clarifying the language we use to foster our vision with our team.

Constructing a great vision, however, is hard work. The team must develop the ability to embrace it, steward it, deepen it, and pivot over time to maximize strategic success. This is particularly important when outside forces shock the environment. These are the three high-level components of a powerful vision that show up in the language of the great leaders of our collective history. They show up in all domains if you look closely enough: politics, human rights, and business. Let’s address these one at a time.

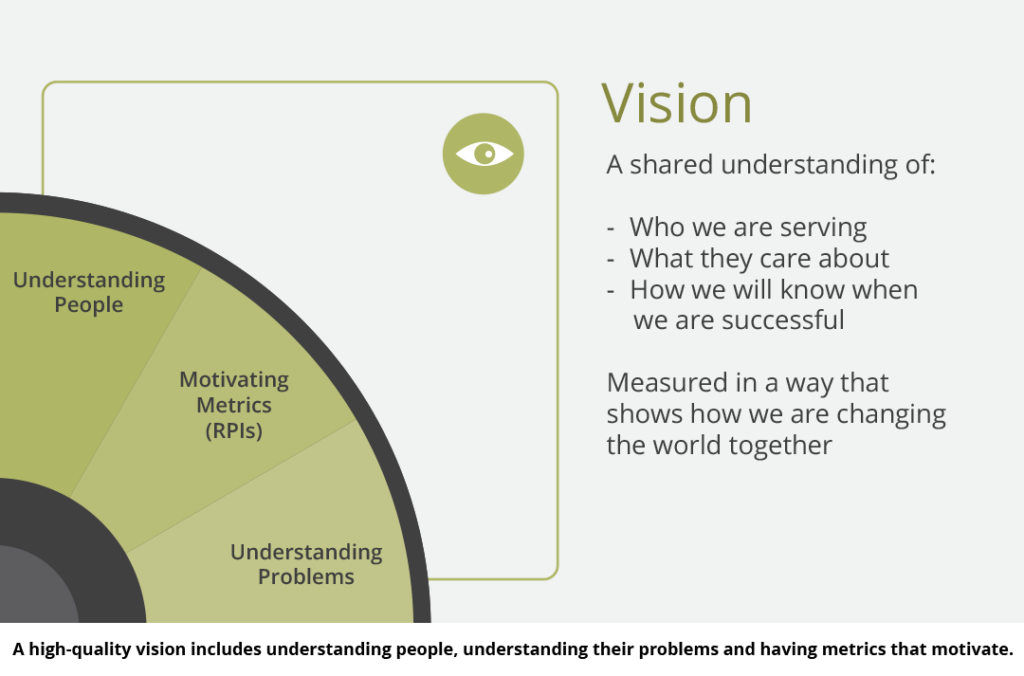

1. People. Only when people have extreme clarity about who they are serving can groups of people dig in to understand why they would care and how they will connect with the problems to be solved.

When groups have this clarity, they also know the priority order of whom they are serving (which includes an understanding of who they are not serving). This is not an easy task. Understanding the complex ecosystem of perspectives associated with any worthwhile vision is constantly shifting and brings layers of complexity. We will dive a little deeper into this later.

2. Problems. With clarity about who is to be served by our vision, the group can determine what problems can and should be solved for them. Ultimately, we want to know what problems this organization is poised to solve that will turn casual customers into passionate advocates.

In psychology, this is called needs satisfaction, and there is a tremendous body of work around this in the academic community. In the business lexicon, it is referred to as “understanding the problem space,” “clarifying the underlying concerns,” “communicating the jobs-to-be-done,” or “articulating the benefits” for your consumers vs. the features.

The key is in the articulation and prioritization of the problems being solved for the benefactors of the organization’s hard work. When it is done well, the group also knows which problems will not be solved. This too is a complex and multi-layered problem, which I dissect in another article. This combination of having clarity around who is being served and what problems are being solved that will turn these people into advocates allows us to communicate unique position in the market. The only thing missing is having clarity around our strategic success.

3. Metrics. Having a clear understanding of what success looks like can be incredibly motivating for people. Articulating a set of clear and objective outcome metrics that demonstrate strategic, as well as tactical, success over time is the final component of a great vision.

People And Problems

A powerful vision for your firm is one that clearly recognizes the need to create great experiences for your customers in the process of solving problems that they care about. When you solve problems by producing a great experience, you build great relationships, and that can be measured through trust, loyalty, and advocacy.

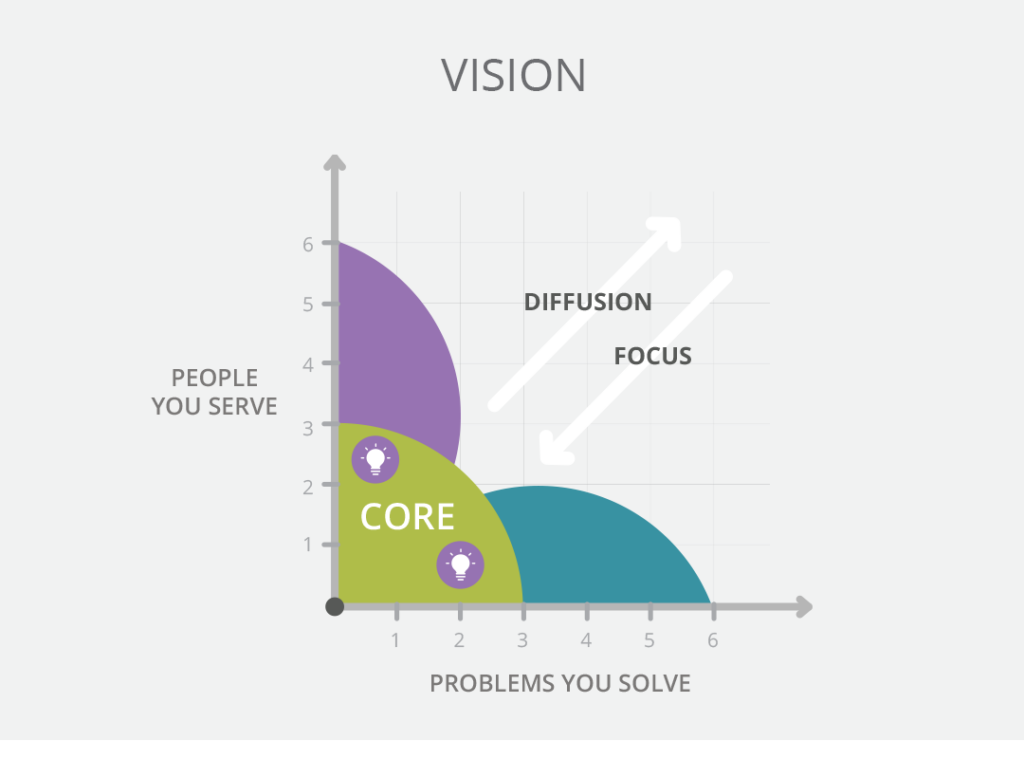

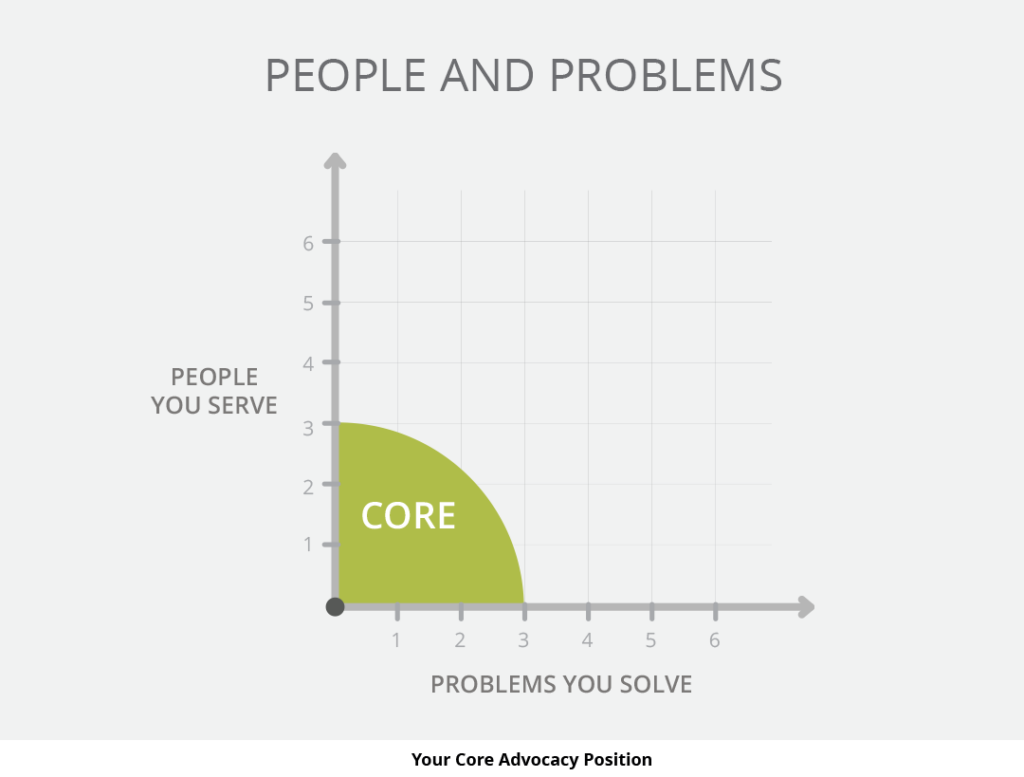

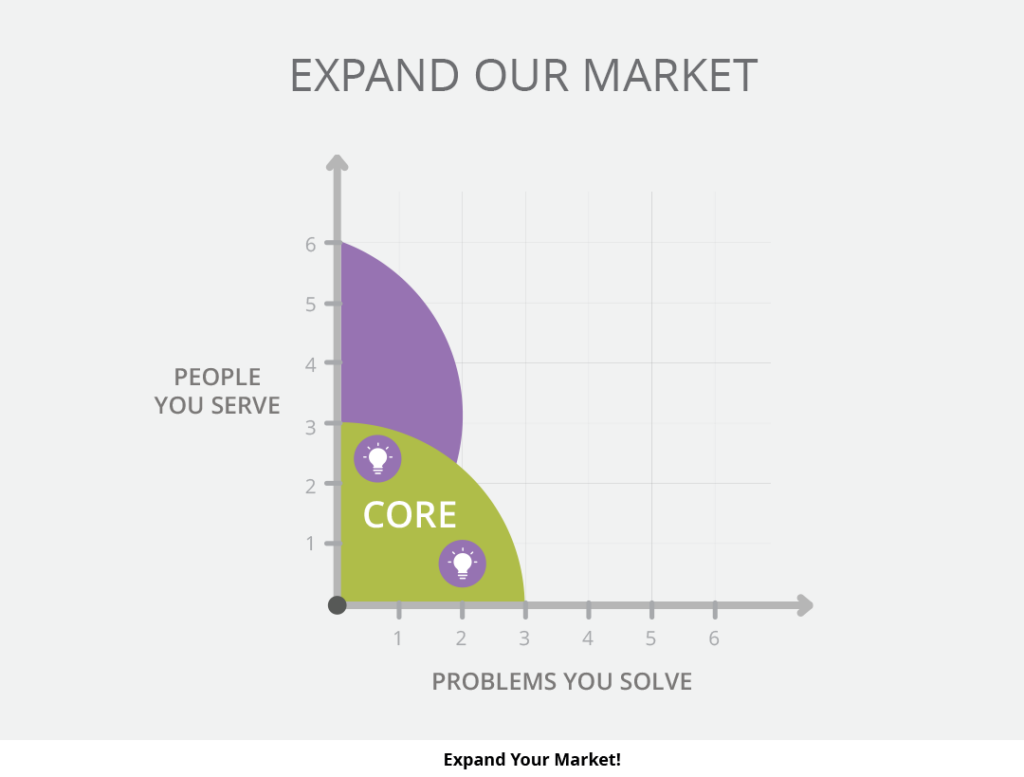

Now, let us take a graphical look at how we might structure our vision. We described earlier that the vision must include a crystal clear understanding of the people in your organizational ecosystem and the problems that you solve for them.

The graph below shows how creating and sustaining focus on your core group of users, through experience, is the key to a great vision. It gives us access to discussing how and when to pivot.

Obviously, your organization cannot solve all problems for all people. What positions your organization and creates the opportunity to generate a profit is your ability to understand, target, and service a group of people who you can turn into your advocates by solving a core set of problems that is valuable to them in the context that you are serving.

Maximizing this equation also requires a distinct understanding of who does not fit this mold. Let’s call this our core advocacy position.

If we were to draw a simple graph that shows the number of persona sets (people) that we serve on the vertical axis and the problem sets that we solve on the horizontal, our core advocacy position would be found in the lower left-hand quadrant of the graph.

As I said before, this is a difficult task. It involves creating clarity around all of the relationships that the organization has to sustain, from employees and vendors to investors and customers. The key to understanding here is that there are a limited number of people whom you can turn into advocates for your organization. Without a clear understanding of who we are here to serve, confusion ensues.

OK, here’s how to graph the equation:

a. Place the subset of customers that you have the most success in creating a sustainable advocacy relationship with, in the number 1 spot toward the core. Place the second most important group of people that you can create sustainable advocacy relationships within the number 2 spot, and so on.

b. Do the same with the problems that you solve for those people with the most important problems on the x-axis in the number 1 spot, and so on. As the graph expands, it becomes easier to see what group of people most of your energy should be focused on.

Note, however, this won’t last forever.

At some point, every organization is faced with great opportunities to expand the core advocacy position. These opportunities come in one of two categories.

The first is to grow the market base. A smart sales executive will inevitably build a relationship with someone who has a problem solved that lies within our domain of expertise, but is outside the current core advocacy position in the upper left-hand range of the chart, shown in purple.

In other words, they want to expand the core set of people that we solve problems for. This sounds exciting. We can take our expertise and expand into a new market segment; theoretically, it shouldn’t create much more work and we will be able to generate more revenue, which will lead to more profit. “An authentic win-win,” says the sales exec.

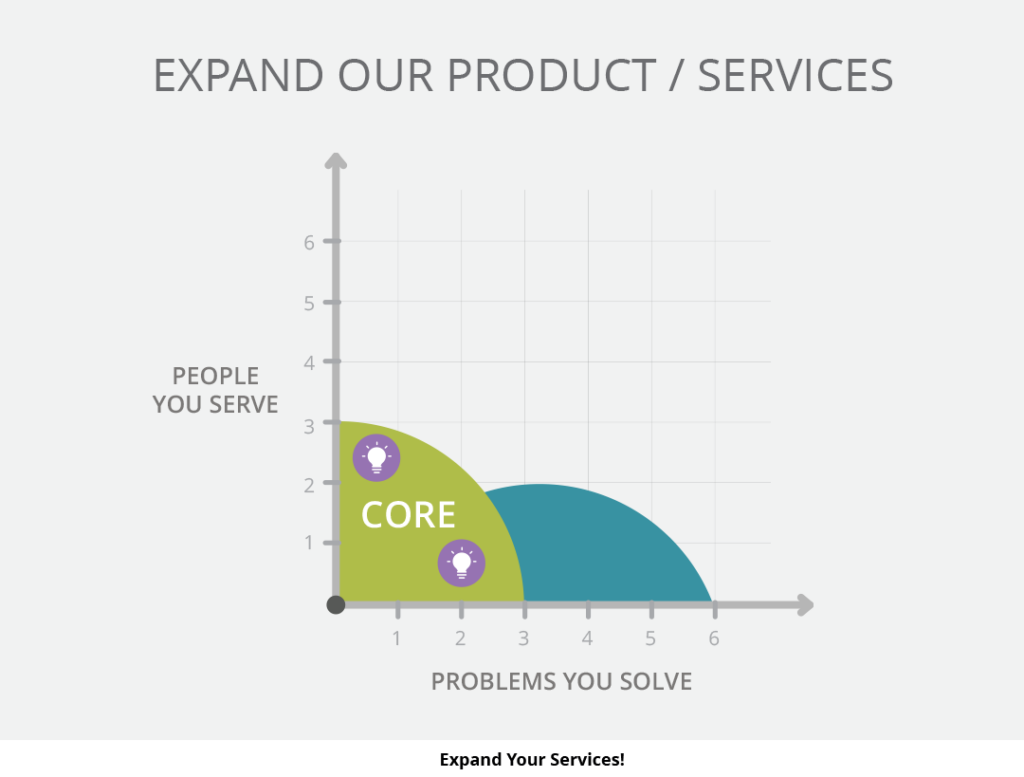

The second opportunity is to solve more problems. In this case, a smart salesperson will have a deep conversation with one of our best customers and uncover a fantastic market opportunity to solve an important (but very different) problem for our existing advocates that will deepen our relationship and, thus, deepen the level of advocacy that we can achieve with them.

On the graph, this will allow us to expand into the lower right-hand quadrant, shown in blue. This sounds awesome. We can learn a new skill, develop a new feature, or provide a new service that will generate more revenue opportunities that will ultimately lead to a more sustainable relationship and long-term profit.

Both are inevitable and necessary for every business, eventually. But these are the kinds of decisions that form the core of your visioning and the essence of your organizational strategy. Changes to how you define your core advocacy position are critical to establishing the right capabilities, the right roadmap, and finding the right people to put on your bus.

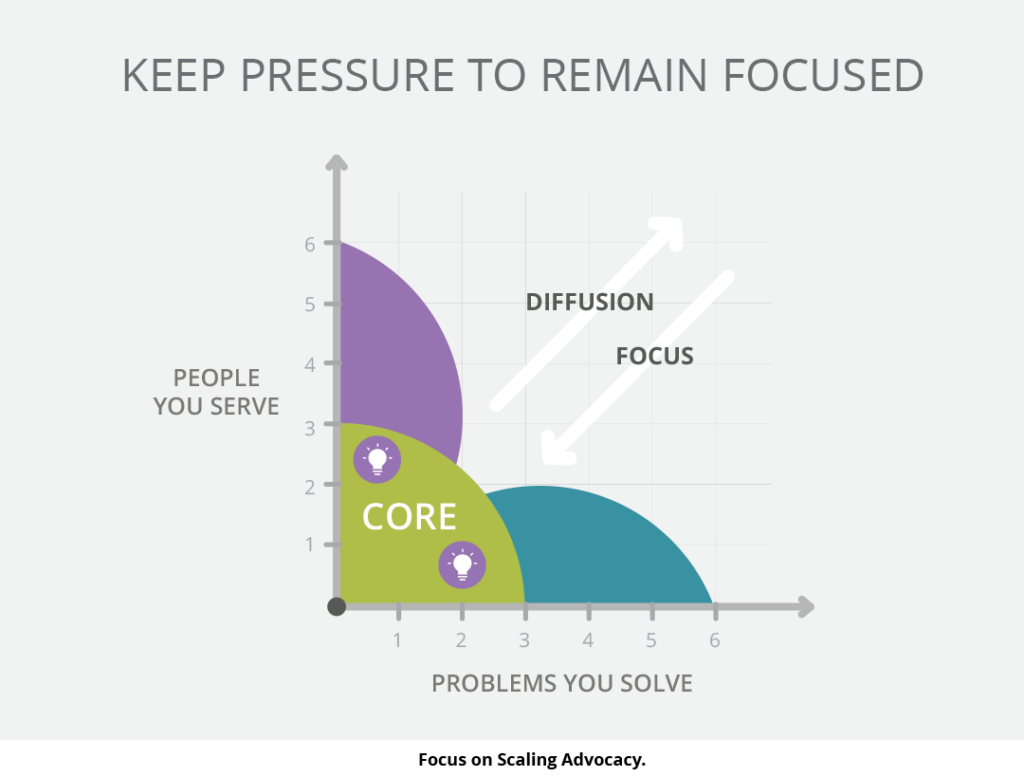

When you pivot your core advocacy position, the ripple effects throughout your business can be profound. There is no way you can take your fixed set of resources and expand your customer base or learn to solve more problems without causing diffusion of your ability to maintain your existing core advocacy position. Every attempt to expand will adversely impact your ability to service the core advocates.

When you point your core capability set at a shiny new target, you lose focus on the market you had. When you invest in learning how to solve new problems, your ability to solve the same problems of the past will inevitably falter.

Sometimes, there is a structural shift that disrupts your market and creates a shock to the system, requiring a pivot. A global pandemic, geopolitical upheaval, regulatory volatility, or another technological disruption, for example, may devastate your existing customer base. You would be forced to either change the way in which your organization solves problems or change course and target a different market.

Other times, a great opportunity might appear that justifies a pivot to maximize the generation of sustainable advocacy. That same structural upheaval might create a market for your products and services where one previously did not exist. It is the ability to see these structural shifts and to capitalize on them that enables great leadership to adjust their focus and create clarity in the face of chaos and uncertainty.

Focus vs. Diffusion

The pattern that shows up in successful organizations lies in the focus.

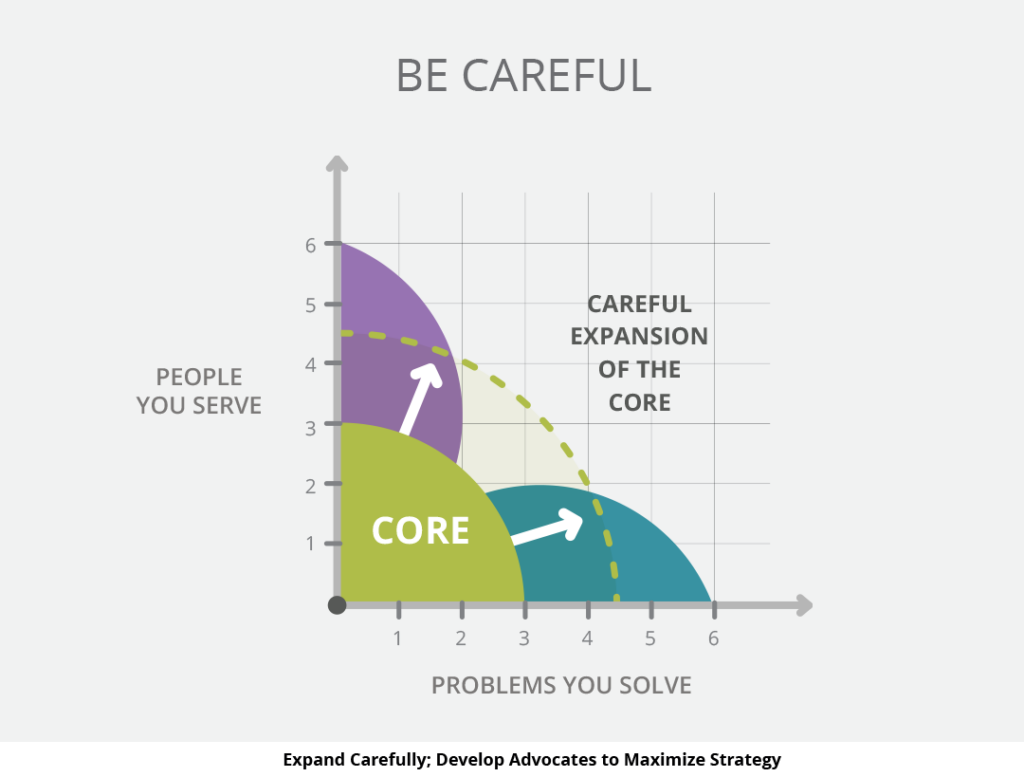

Great leadership teams make these shifts carefully and purposefully with their core advocacy base in mind. When they expand, they work to only expand with minimal impact on their historical core advocacy position while opening up opportunities for future advocates. They serve to expand the total number of advocates and the depth of advocacy that they are able to create through their expansion or through their shifts.

Another pattern that this shows represents a problem that all business leaders share. Pareto’s law applies to an organization’s customer base in that 20% of the customers you have often cause 80% of the headaches. The reason for this is that firms lack a concise understanding of the problems they solve in a way that matters to those they have turned into advocates. If they did, it would be obvious which customers should be avoided (or fired).

If the team can figure out how to avoid taking on more of the 20% whose problems we seem unable to solve, the organization can become much more efficient. There will always be some customers that none of us wants; they don’t value the same things we do, and despite every effort we can’t seem to make them happy. We sometimes chase these customers because their money is green, and we think we can capture a lot of revenue. However, if the organization cannot turn these customers into advocates, in time, our culture will be diluted and we will end up reducing our capacity to serve our core advocates and deliver on our vision.

The better we know the people we serve and the problems we solve, the more empowering our vision will be. When our vision is paired with a motivated team, aligned on the same human-oriented goals, we have a complete strategy to steward that will help us maximize the number of advocates that our organizations create, together.

References and Further Reading:

Business is High Art — A Birds Eye View of Culture

Greatest Leaders of Our History

Competing Against Luck by Clayton Christiansen

Measuring Relationships, Organizational North Stars

Objective Prioritization is Impossible

Inspiring Indicators of Success

Ryan, R. M., Sheldon, K. M., Kasser, T., & Deci, E. L. (1996). All goals are not created equal: An organismic perspective on the nature of goals and their regulation. In P. M. Gollwitzer & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action: Linking cognition and motivation to behavior (pp. 7–26). New York: Guilford Press.

The Handbook of Self Determination Theory (2004) by Ed Deci, Richard Ryan and Others

Sean Flaherty is Executive Vice President of Innovation at ITX, where he leads a passionate group of product specialists and technologists to solve client challenges. Developer of The Momentum Framework, Sean is also a prolific writer and award-winning speaker discussing the subjects of empathy, innovation, and leadership.